IN THIS ISSUE

Record Growth for Aquatic Grasses in the Bay

New Science Center focuses on the Potomac

ICPRB joins the Cleanup Effort

ICYMI, George Washington’s Bathtub

We share the #PotomacLove

When it Rains, Salinity Falls

The waters of the Potomac are again receding from flood levels after several late-May and June storm systems, although damage (and maybe some benefits) will continue for some time. The flooding in the upper Potomac basin brought large amounts of sediment and nutrients into the river that can provide the food needed for algae blooms later this summer. The flows, which included numerous stormwater and sewer backups, also can cause some short-term spikes in bacterial levels. These conditions can stress aquatic animals and plants, as well as restricting recreational use. Roads and other infrastructure also sustained damage in the upper basin and Shenandoah watershed.

As flood waters move downriver, they affect salinity and oxygen levels in the tidal river, stressing aquatic communities. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission are concerned about effects on oyster populations near the Route 301 Bridge that crosses the Potomac near Colonial Beach, Va. Oyster restoration efforts are being stressed by the lower salinity levels caused by the massive freshwater input from upstream, as well as how these flows may cause stratification between the fresh water moving downriver on the surface and the heavier, saltier water moving upstream on the tide. This stratification can deplete oxygen levels near the bottom, and future algae blooms that die and fall to the bottom to decompose (oxygen is used in decomposition) will intensify the problem for the oysters, which need both salty water and oxygen. These conditions can favor the growth of plants that like freshwater at the expense of plants that prefer saltier water. This interaction highlights the complex ecology of the Potomac River, where salt and oxygen levels can change rapidly in response to flow and weather conditions. These effects also influence the growth of aquatic plants (see related article), fish spawning runs, and other ecological aspects.

While these episodes of deluges and dry weather can’t necessarily be blamed on climate change, ICPRB research using climate change models to predict future water availability found that many of the models did agree that weather events in the basin would become more extreme. These weather events come at a time when basin water quality is improving in many aspects, but is still fragile enough for weather patterns to exert a powerful effect.

The Potomac River: A Story of Love, Loss, and Redemption

During one of the first warm days of the year, a group of people gathered in the heart of the District of Columbia. Forgoing the sun and warmth, they sat in a conference room at the Smithsonian Institution’s S. Dillon Ripley Center to learn about the backdrop to the nation’s capital and the source of our drinking water: the Potomac River.

During one of the first warm days of the year, a group of people gathered in the heart of the District of Columbia. Forgoing the sun and warmth, they sat in a conference room at the Smithsonian Institution’s S. Dillon Ripley Center to learn about the backdrop to the nation’s capital and the source of our drinking water: the Potomac River.

Just like the plot of a romantic novel, the visitors learned of the (ecologically) rich and beautiful Potomac as seen by the original inhabitants and the first European explorers. They learned of the struggles the Potomac experienced due to neglect, pollution, and overharvest. Finally, our river heroine sees hope in the future and a revived love from the community.

“Washingtonians are paying attention to the fact that we are a river city in a way they haven’t in the past,” exclaimed Rebecca Roberts, program coordinator for the Smithsonian Associates, the event organizer. Roberts said it was the newly renewed love affair with the river that was the inspiration for the event, titled, “The Potomac: Rolling Through DC’s History and Heart.”

Watery Highway to the West

The morning started out with a look through the river’s storied human history with a presentation by author and historian Garrett Peck. He let us in on a secret: contrary to popular belief, the city of Washington, D.C. was not built on a swamp. Its residents will need to blame the humidity on something else from now on.

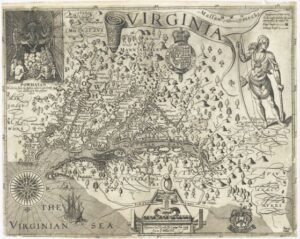

According to Peck, the Potomac River was thought by the English explorer Captain John Smith, to be a passageway to the Pacific Ocean. He found it teeming with life. Indigenous peoples lived along the river, relying on its abundant aquatic life for sustenance throughout the year. Over a century later, George Washington also saw the river as a watery highway to the west, envisioning a system of canals that could easily move people and goods up and down the river. Alas, the canal system was beat out by the cheaper and more efficient railroad system and the rest, as they say, is history.

Peck went onto explain that even with the failed canal system, the river was still an important mode of transportation. The Alexandria port was once the 5th busiest port on the east coast. There were several more ports in the Washington, D.C. area that could accommodate deep, ocean-going vessels. Tobacco farms and other anthropogenic activities upstream have since filled these ports with so much sediment that now, during low tide, you are more likely to walk on them than to navigate a boat.

Smash together, break apart, smash together, etcetera, etcetera

Callan Bentley, assistant professor of geology at Northern Virginia Community College, walked the audience through the geological mega-history of the area. The six different geological regions in the Potomac River basin each tell their own story. A colorful GIF featuring the six regions can be found on Bentley’s Twitter feed. A billion years ago, the Potomac River basin was part of a pre-Pangea supercontinent known as Rodinia. The orogeny (the technical term for tectonic plate action) of the continents forming, tearing apart, smashing together again to create Pangea, then breaking apart once more created the mountain ranges in the west of the basin.

The oldest geologic formation in the basin is Old Rag Mountain in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Old Rag Granite that this mountain sits upon was crystallized during the formation of the supercontinent Rodinia.

The love affair with the Potomac River celebrated by John Smith, George Washington and so many others that lived along its shores took its toll on the river itself. Sediment, pollutants, sewage, harvesting and damming decreased aquatic animals and plants, making the river a toxic brew in places.

A River Renewed

Just as many storybook romances contain a tale of struggle and loss before a victorious ending, so too, did the people of the Potomac River basin. A renewed outcry from the basin’s residents lead to new legislation, new technology and infrastructure that reduced sewage output, and efforts across the basin lead to a cleaner Potomac river. Organizations like the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin worked tirelessly for a cleaner, healthier river.

The river’s progress has been followed closely by Chris Jones of George Mason University (GMU), a speaker at the Smithsonian Associate’s event. Since 1984, scientists at GMU have been monitoring the water quality and biological communities in Gunston Cove, an embayment of the tidal freshwater Potomac River. At the event, Jones spoke of improved water clarity and the return of submerged aquatic vegetation, and general ecosystem recovery over the last couple decades. This trend is associated with a reduction in phosphorous loading due to process changes in the wastewater treatment plant located along the shores of the bay.

A similar recovery has been seen upriver of Gunston Cove, claimed Claire Buchanan, Aquatic Biologist at the Interstate Commission of the Potomac River Basin, another speaker at the event. Her presentation started with an explanation of the abundance of fish and wildlife and the many deepwater ports along the river in the years before sediment and pollutants muddied the waters. Oysters, mussels, and underwater grasses abounded. Although progress has been made, that abundance of life has not returned and probably never will. Once an ecological regime shift passes a critical threshold, it is very difficult to return to the previous status.

The river may not return to the golden era of abundance, but many are working towards a cleaner future. The final speaker at the event was Carlton Ray of DC Water, the water utility that provides drinking water to D.C. residents and provides wholesale wastewater treatment services to 2.1 million people in the Washington Metro Area. As part of the utility’s Clean Rivers Project, the combined sewer overflows, that have heavily polluted the Anacostia and Potomac rivers in the past, will decrease by 98% by the year 2023. The first phase of the project, the Anacostia River Tunnel Project, came online March 2018. The second phase, the Potomac River Tunnel Project, is underway. Due to projects like these and many others, the Anacostia River, once known as the Forgotten River, is no longer left behind. Its resurgence was noted in a recent WAMU article.

Changes are being made. Fish are returning, dissolved oxygen is improving, and sewage is decreasing. There are even discussions of allowing people to swim in the waters in the next few years. We are on our way to a new era in clean water, a new regime. There is hope for the river still.

Record Growth for Aquatic Grasses in the Bay. The Potomac, while Healthy, had Setbacks.

An estimated 104,843 acres of underwater grasses were mapped in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries in 2017, according to the Chesapeake Bay Program. It is the highest total amount ever recorded and the first time that total abundance has surpassed 100,000 acres since monitoring began. It was the third consecutive year of record-setting growth.

The Bay total is more than 14,000 acres greater than the 2017 restoration target, and 57 percent of the ultimate restoration goal under the Chesapeake Bay Program. The total increased by five percent from 2016 to 2017.

Changes in weather and runoff

The increases have resulted both from the weather conducive to plant growth and from reductions in nutrient loadings both from reduced precipitation and the success of efforts under the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL). Both modeling and monitoring results during the past several years have documented decreases in nutrients that suggest that the many efforts to reduce nutrients and sediment under the Bay TMDL are bearing fruit. Reducing nutrients is a key factor in promoting aquatic plants, which like their land-based cousins, require sunlight to grow. Excess nutrients feed algal blooms that decrease water clarity and the sunlight available to the plants. In addition, some algae attach to plants and further block sunlight. In a positive feedback cycle, as plants become established, they consume nutrients in the water and trap sediment and thereby increase water clarity.

Different species of plants populate the bay watershed, and the kinds of plants found in a particular area are related to the saltiness of the water. There are several “salinity zones” in the bay with boundaries that move somewhat seasonally and with rainfall. The Bay Program examined abundance by salinity zone. They noted that the tidal freshwater area grew during 2017, achieving 96.5 percent of the zone goal. Slightly salty waters (oligohaline) fell slightly, moderately salty waters (mesohaline) rose somewhat, achieving 51 percent of the goal, with the bay’s very salty waters (polyhaline) also registering an increase.

Closer to Home

Closer to Home

While this is great news overall, the Potomac watershed was hardly mentioned in press releases from the Bay Program or Maryland. The Potomac didn’t fare as well as some other regions of the bay, although the good news is that areas of the watershed were already doing quite well.

The Anacostia River in the District of Columbia, part of the Potomac’s tidal freshwater region, held about 13 acres of plants in 2017, up almost 60 percent from the previous year. No plants were found upstream in the Maryland portion of the Anacostia, which has not held plants since monitoring began and has no coverage goal under the Bay Program. The Potomac River in the District decreased slightly in 2017 but still meets its plant goal. The Maryland portion of the tidal freshwater Potomac doubled its acreage from last year and is close to meeting its goal. The Virginia side of the river decreased slightly from 2016 but is already meeting its goal.

A little further downstream, Piscataway and Mattawoman creeks continue to hold rich beds of aquatic plants, and Mattawoman Creek, despite a slight decline, is not far from its goal. Piscataway remains at about 50 percent of its goal. Piscataway Creek was one of the first tidal Potomac tributaries to hold extensive hydrilla beds in the 1980s, but plant populations have wildly fluctuated. Its preliminary 2017 acreage was about 347 acres. It held about 523 acres in 2010, declined, hit 541 acres in 2015, and has declined again. In general, aquatic plant communities experience boom-and-bust cycles, although not as extreme a what is seen in Piscataway Bay.

The Potomac’s slightly salty (oligohaline) waters, which run from downstream of the Occoquan area to the Route 301 Bridge, experienced strong decreases of plants. Bob Orth, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science professor who conducts the annual bay surveys, noted that the extended dry period could be a major reason for the die-off. Salt-tolerant freshwater plants have been growing in the sector, and more than a year of drought conditions (preceding the frequent rain events of spring 2018) have increased the salinity and stressed the plants.

The Potomac’s moderately salty (mesohaline) waters fared well, as did many of these areas in the bay. Expansion of eelgrass beds in these regions have grown during the last several seasons.

The Potomac River, with more than 100 miles of tidal river will usually show a wider range of conditions because of its multiple habitats.

Overall, “2017 was quite an exciting year for the survey. First, we exceeded 100,000 acres for the first time ever in the survey, and now have three successive years of record high numbers. Second, we noted submerged aquatic vegetation in two areas of the bay that had not seen any since 1972 (in front of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Laboratory in Solomons, Md., and in the upper Choptank near Mumfort Island, Va.). Hopefully, this trend will continue in 2018.” Orth said.

To learn how to identify different aquatic plants check out the previous Reporter article, Common Plant Species found in the Potomac River.

New Science Center focuses on the Potomac

A large crowd gathered in Woodbridge, Va., on April 12, a rare warm spring day, to celebrate the opening of George Mason University’s Potomac Science Center on Belmont Bay. The new 50,000-square-foot complex will house the Potomac Environmental Research and Education Center (PEREC), a unit of the university devoted to environmental research on the Potomac and aspects of aquatic science, and include facilities for general environmental science and programs for teaching science to visiting area school groups. The facility meets LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Silver certification standards.

The Potomac Science Center’s unique focus on the river makes it a valuable new asset for the basin. The university began that focus decades ago with continuing research on aspects of Belmont Bay and the Potomac and Occoquan rivers, and an overall emphasis on tidal freshwater habitats. Its most comprehensive effort is an ongoing study of the ecology of nearby Gunston Cove. Water quality, wildlife, and plant data have been collected at the cove for more than 30 years.

The center has been a dream of PEREC Director Prof. R. Christian Jones for many years, and the new facility, with its beautiful waterfront location, modern building with gleaming new labs and class spaces is impressive. The new facility will invite partnerships with other institutions of all types, and make PEREC a leader in increasing understanding of the ecology of the tidal Potomac River.

PEREC’s Prof. Cindy Smith, the K-12 Education and Outreach Director, led a group through the facility, highlighting both the laboratories with spectrometers and chromatographs, as well as classrooms and simpler tools that have helped her host area school groups in environmental education programs. Since 2009, PEREC has delivered watershed education to more than 40,000 Prince William County and 25,000 Fairfax County school students. The new center will help PEREC to provide even more opportunities for area schools, Smith noted.

The next phase of development will include an enlarged pier providing deepwater access for research boats and as a platform for visiting school students to conduct experiments. The ICPRB congratulates our colleagues at PEREC and welcomes these new resources aimed at protecting and improving the Potomac.

ICPRB joins the Cleanup Effort

In the Potomac river basin, the month of April is known for light rain, spring flowers, and picking up trash. So. Much. Trash. More than 340,000 pounds of it.

In the Potomac river basin, the month of April is known for light rain, spring flowers, and picking up trash. So. Much. Trash. More than 340,000 pounds of it.

The Alice Ferguson Foundation has organized the Potomac Watershed Cleanup every April for the past three decades. Out of interest and need, the original one-day event has turned into a month-long lineup of river cleanups of all shapes and sizes throughout the watershed.

The Alice Ferguson Foundation has organized the Potomac Watershed Cleanup every April for the past three decades. Out of interest and need, the original one-day event has turned into a month-long lineup of river cleanups of all shapes and sizes throughout the watershed.

This past April, 9,700 people participated in the cleanup events, picking up all kinds of trash, including tires, plastic bags, and the recent poster-child of harmful litter, plastic straws.

The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin organized two events during the month of April. One in Frederick, Md. and one in Herndon, Va. There were 26 bags of trash picked up by 18 volunteers of all ages. We would like to thank those who joined ICPRB and other organizations to clean our streams and rivers!

You don’t have to wait until next April to cleanup the river. Picking up trash is an easy way to protect our drinking water. Much of the trash along the road ends up in storm drains which can flow directly into your local river or stream. Why not take it a step further and go plogging? This is a new trend that combines jogging and trash pickup.

ICYMI

During the summer months, ICPRB publishes a weekly column, About the Basin, that introduces readers to fun and interesting places around the Potomac River basin. In case you missed it (ICYMI), a recent article about the only outdoor monument to presidential bathing, George Washington’s Bathtub, really caught the public’s attention!

During the summer months, ICPRB publishes a weekly column, About the Basin, that introduces readers to fun and interesting places around the Potomac River basin. In case you missed it (ICYMI), a recent article about the only outdoor monument to presidential bathing, George Washington’s Bathtub, really caught the public’s attention!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to catch future editions of About the Basin.

Potomac Love

This past Valentine’s Day we saw a lot of love from ICPRB Commissioners and staff when they participated in a #PotomacLove event across social media declaring why they love the river. Watch their stories in the video above. Then post your own #PotomacLove story on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.

Looking for up-to-date information on the Potomac River basin? Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our Newsletter!