On June 8, 2022, the U.S. House passed HR 7776 that would authorize the federal government to conduct a feasibility study for recreational access, including “enclosed swimming areas,” in the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers.

An historical look at swimming in the Potomac River

Human contact with the Potomac River predates recorded history and has been continuous through the present day throughout the basin with the exception of the waters of the District of Columbia.

The river in the District has long suffered the strain of a concentrated population and the subsequent pollution it creates.

But the Potomac River has shown its resilience and times are changing. The U.S. House recently passed a bill that authorizes a feasibility study of enclosed swimming areas in the District’s rivers. The D.C. Department of Energy and the Environment is looking at updating regulations, water quality standards, and monitoring practices. D.C. Water’s massive infrastructure rebuild, the Clean Rivers Project, is expected to reduce combined sewage overflow by 96%. Organizations like Potomac Riverkeeper Network and Anacostia Riverkeeper are working hard to gather the data as well as change the tide of public opinion for swimming in D.C. waterways. Here at ICPRB, we know the public is curious because we get asked throughout the summer, “Is it Safe to Swim in the Potomac“?

It has been decades in the making, but it is apparent that we are approaching a watershed moment for swimming in District waters.

So, let’s explore a century of policies, engineering, and advocacy that got us to where we are today.

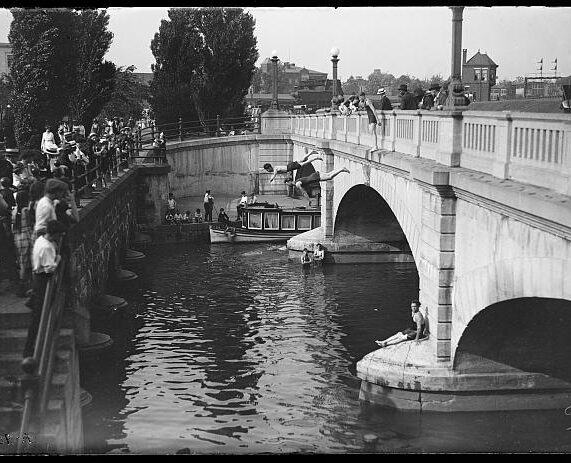

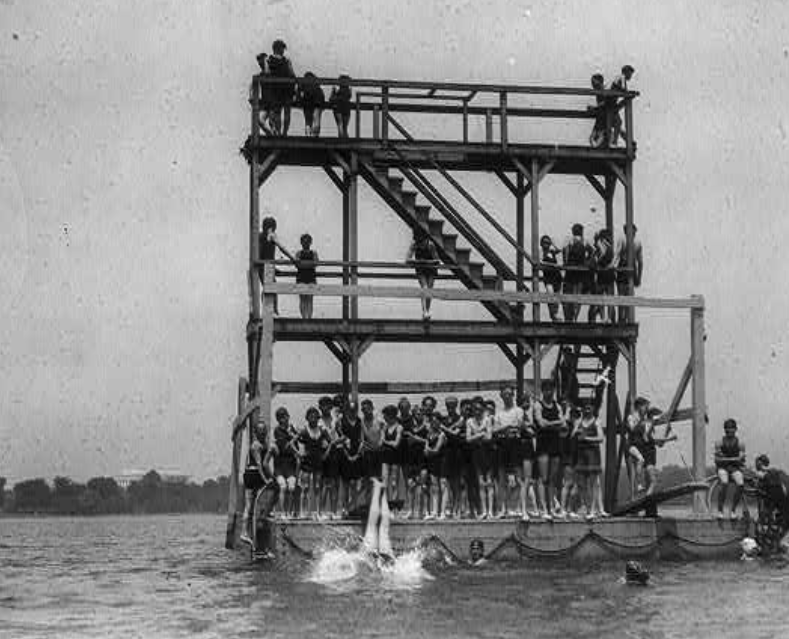

The growing population of the early 1900s used the waterway for waste disposal—human waste, industrial waste, agricultural waste—it all went in the river. As the population continued to increase, the tidal waters of the District grew increasingly worse. The tidal basin and other areas were popular swimming holes in the early part of the century until legislation restricting swimming began in the early 1930s. See below for a slideshow of photos highlighting the summer fun of the roaring ’20s

The population of the metropolitan area doubled in the 1940s, the same decade that ICPRB was established. The ICPRB’s first order of business was to collect data for the basin’s initial assessment. ICPRB was tasked with answering the question, “How bad was it and why?” The study found that the vast majority of the river’s population was served by primary sewage treatment, which means that only solids were removed from raw sewage. The report also noted the importance of the river in people’s daily lives through recreation, fishing, and transportation.

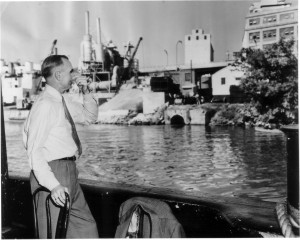

1953: Senator Wayne Morse holds his nose against the stench of the Potomac River near Georgetown. (ICPRB)

The 1950s opened with an ICPRB report that noted the entire river was unsafe for drinking, questionably safe for swimming upstream of Great Falls, questionably safe for recreation between Key Bridge and Haines Point, and the river downstream in the District was unsuitable for any purpose. A 1954 ICPRB report on DC-area water pollution helped inform a 1957 U.S. Public Health Service declaration that the Potomac in the District was “unsafe for swimming.” The report and pronouncement were important in leveraging authorization of public works and sewerage expansion that would begin to address the sewage problem.

In the 1960s, swimming and eating fish caught from river shore remained illegal, but the public continued to look toward the river. Lady Bird Johnson donated an elegant floating fountain that shot high up into the air in the Potomac River. During high winds the fountain was turned off due to fears the spray would douse the National Airport with cholera germs. The fountain was eventually deemed a public health hazard for spraying high levels of coliform bacteria onto the nearby park. Events like these increased public consciousness and activity. The decade saw the federal Water Pollution Control Act, Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” and growing stewardship. Both federal and local laws were pushing for greater water quality.

The 1970s saw continuing improvements to water quality in the metropolitan area and nationwide with the passing of the Clean Water Act and later amendments. The act guided federal money and restoration efforts, primarily in improved sewage treatment. The era saw increased public interest and pressure for better water quality. Residents of the District wanted to be close to the river in ways that were still in practice both upstream and downstream. Yet, D.C. water quality, including huge annual mats of blue green algae, resulted in a water contact prohibition by the D.C. Council in 1971. The growing public interest in a healthier environment in the 1970s kept the pressure on to clean up metropolitan waters. Riverfront signage in D.C. and down to Mount Vernon warned people to avoid contact with the water and to wash pets that came in contact with it.

Lady Bird Johnson’s Potomac River fountain that was eventually deemed a public health hazard. (ICPRB)

Yet, there was hope. Annual algal mats declined during much of the decade, and largemouth bass returned to the river along with the return of bass guides who targeted D.C. waters.

Citizen interest in the river and the waterfront continued to build in the 1980s. The interest in the river’s health grew alongside interest in revitalizing the metro waterfronts and improved access. The effort was boosted by a National Marine Fisheries Service report on waterfront revitalization. The ICPRB, along with several federal agencies and some waterfront businesses formed the Washington Area Waterfront Action Group (WAWAG). The ad hoc organization sought to leverage revitalization interest along government-controlled land and sought ways to create a better public experience along the waterfront.

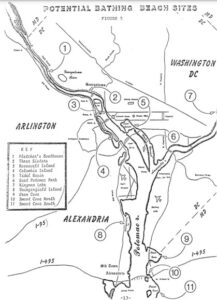

The WAWAG worked to transform the moribund Washington waterfront in many aspects. One was a task force to address swimming and other water contact recreation. The group held a press conference on bathing beaches and created a list of possible sites for bathing beaches along the metro river. The group’s efforts helped inspire other efforts. Windsurfers in the District were angered that the boards were considered water contact, and so they held a press conference in which a number of windsurfers dressed in business suits and brought attaché cases aboard. This televised water rally proved that windsurfing was not necessarily a water contact sport, similar to canoeing and kayaking. A 1982 WAWAG report offered suggestion for potential “bathing areas” in the District.

The beginning of the Potomac Riverfests in D.C., and similar efforts in Alexandria and other communities became annual affairs.

Rambling Raft festivals were begun in D.C. Unfortunately, a resurgence in summer algae blooms and other considerations halted some of these events.

The wave created by WAWAG and other groups continued to grow, and demand for swimming remained an issue. In the early 2000s, ICPRB was approached by the Nation’s Triathlon, which was creating an event in D.C. The ICPRB helped direct them to the proper officials in D.C. government to get a permit for a swimming section off the National Mall. The permit required them to monitor the water for a month before the event to ensure acceptable water quality. The swim portion was cancelled several times during the event’s several years of running due to the stringent water quality requirement.

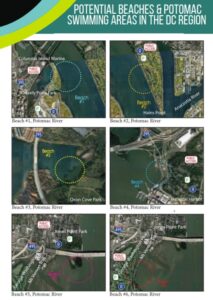

Now, Potomac Riverkeeper Network (PRN), Anacostia Riverkeeper, and other groups conduct weekly water quality monitoring to promote swimming and river recreation. Many of the test sites get the swimming “thumbs up” when the data is published at www.theswimguide.org. Just like the WAWAG report in the 1980s, the recent report published by PRN, Swimmable Potomac Report 2022, proposed several areas for public beaches in the future.

As the health of the river has improved over the eight decades since ICPRB was created, ICPRB has worked alongside government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and the public to increase access and stewardship to our Nation’s River. We look forward to seeing D.C. residents and visitors take a cooling dip in the river on a hot summer day. As Lord David Attenborough says, “No one will protect what they don’t care about; and no one will care about what they have never experienced.”